Assassination of King Faisal: Unraveling the Crime’s Intricacies 1

Watan – In 1951, Paris’s streets showcased a peculiar event. At the “Fountain of the Innocents,” a renowned city landmark, Parisians gathered, entranced by an odd display. A young man, devoid of clothing, wielded a sword and danced under the fountain’s cascades. His companions, garbed in unfamiliar clothing, attempted to shield him and deter his performance. He evoked images of an ancient Knight Templar, feigning insanity to evade heresy charges or perhaps a wanderer from Paris’s catacombs. The spectacle concluded when French police detained him. To many’s surprise, authorities identified the young man as a member of the Saudi royal family, specifically King Abdulaziz Al Saud’s son. This revelation connected him to the oil-rich nation that had captivated France and its allies. Recognizing his royal status, officials returned him to his father.

This prince, Mosaad bin Abdulaziz, faced his father’s stern repercussions, especially after the incident dominated French headlines. King Abdulaziz incarcerated the prince for an extended duration and prohibited him from international travel as well. This punishment deepened the rift between them, relegating Prince Mosaad to the list of disgraced princes.

A Royal Conspiracy and Modernization Resistance

In 1965, a faction of Wahhabi clerics persuaded Khalid bin Musa’ad, the son of the infamous dancing prince, to oppose a forthcoming television station in Saudi Arabia. Prince Khalid, harboring familial resentment, seemed to continue a trend prevalent in the Al Saud lineage.

Prince Fahd, then Minister of Interior, sent a specialized unit under Mohammed Hilal Al-Mutairi to arrest Khalid. Rumors suggested that Prince Fahd had sanctioned Khalid’s elimination. After a gunfire exchange, Prince Khalid met his demise.

Prince Musa’ad sought justice for his son’s death. However, Prince Fahd declined, asserting that the officer had merely executed his duty. King Faisal, feeling constrained by the situation, compensated Prince Musa’ad with significant blood money and an additional sum to acquire a Lebanese palace.

On March 25, 1975, another of the dancing prince’s sons, Faisal bin Musa’ad bin Abdulaziz, entered the royal court in Riyadh. Scheduled to meet King Faisal and the Kuwaiti Oil Minister, Abdul Muttalib Al-Kazemi, the armed prince, unchecked by security, confidently approached the king and fired three fatal shots.

The assassination’s aftermath was rife with inconsistent narratives, naive accounts, and hourly evolving stories. Four official statements emerged on the day of the incident alone. Reuters, citing a senior family member, even reported the assassin prince’s death.

The Kuwaiti Oil Minister, Abdul Muttalib Al-Kazemi, remained the sole consistent witness, despite Prince Nayef’s warnings against discussing the event. His account, though brief, held credibility.

The assassination’s secrecy initially seemed security-driven, but this silence has endured for 48 years.

In a 2004 Al Jazeera interview, “Khaled Khodr Agha” hinted that “Sam Al-Zakhem” had informed him of Prince Fahd sending the assassin prince, Faisal bin Musa’ad, to Colorado for “brainwashing.” Al-Zakhem, a prominent U.S. figure and former Bahraini ambassador, never refuted this claim.

The Aspen Institute Connection

The gravity of this narrative demands serious consideration. The Aspen Institute in Colorado, known for mind control and manipulation operations, and where “Sam Al-Zakhem” resides, strengthens this conviction. The institute’s ties extend to the U.S. government, its intelligence agencies, and its primary funder, the Rockefeller family. This family previously employed Henry Kissinger, who later transitioned into politics under Presidents Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford. So, did the prince have connections to this institute?

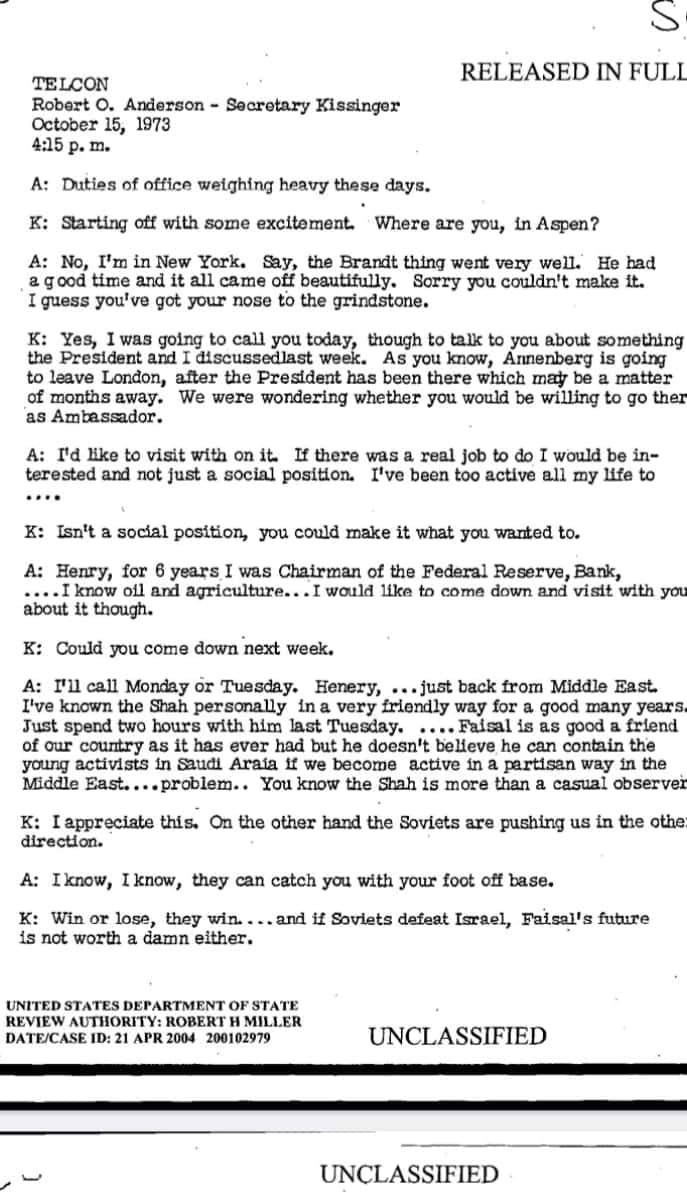

A hint about King Faisal’s potential elimination surfaced nine days before the October 1973 war. In a conversation between Robert Anderson, the Aspen Institute’s head, and Henry Kissinger, Anderson conveyed King Faisal’s concerns. Kissinger’s response indicated that if the Soviets triumphed over Israel, King Faisal’s future would be bleak.

While Christina Surma’s intelligence role remains plausible, the Venezuelan Carlos’s inclusion in the assassination narrative appears fabricated. Carlos, known for his affiliations with the “Sudairi wing in Saudi Arabia,” received significant payments for various tasks and to safeguard their Lebanese interests.