Egypt and the UAE: A Hidden Power Struggle Amid Sudan’s Civil War

As Sudan descends into chaos, Cairo and Abu Dhabi find themselves on opposing sides, shaping the war’s outcome and the region’s future.

Watan-Amid the devastating civil war in Sudan, a less visible but equally significant power struggle is unfolding between two regional powers: Egypt and the United Arab Emirates.

Egypt supports the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF), while the UAE backs the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) in the war that erupted on April 15, 2023. Nearly two years of fighting have resulted in a catastrophic humanitarian crisis, pushing Sudan toward complete collapse.

In its final days, the Biden administration imposed sanctions on both RSF leader General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (Hemedti) for his command responsibility over forces accused of genocide, and SAF leader General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan for obstructing peace efforts, blocking aid, and allegedly using chemical weapons.

Despite mounting evidence from UN and US investigators indicating that the UAE is heavily involved in supporting the RSF in Sudan’s war, Abu Dhabi continues to claim neutrality as a humanitarian actor. However, this claim has been directly challenged at the highest levels of the US government.

During his Senate confirmation hearing, Secretary of State Marco Rubio explicitly accused the UAE of “supporting an entity that is openly committing genocide.”

Egypt’s role in backing the SAF and the military-led government in Port Sudan has become increasingly apparent.

In September, Egyptian Foreign Minister Badr Abdel Aty emphasized “the importance of not placing the Sudanese national army in the same category as any other party.”

Abdel Aty recently reaffirmed Egypt’s commitment to “supporting the capabilities of the Sudanese army” in coordination with its emerging security partners in the Horn of Africa, Eritrea, and Somalia.

Despite their alignment on most regional issues, Egypt and the UAE find themselves on opposing sides in Sudan’s war.

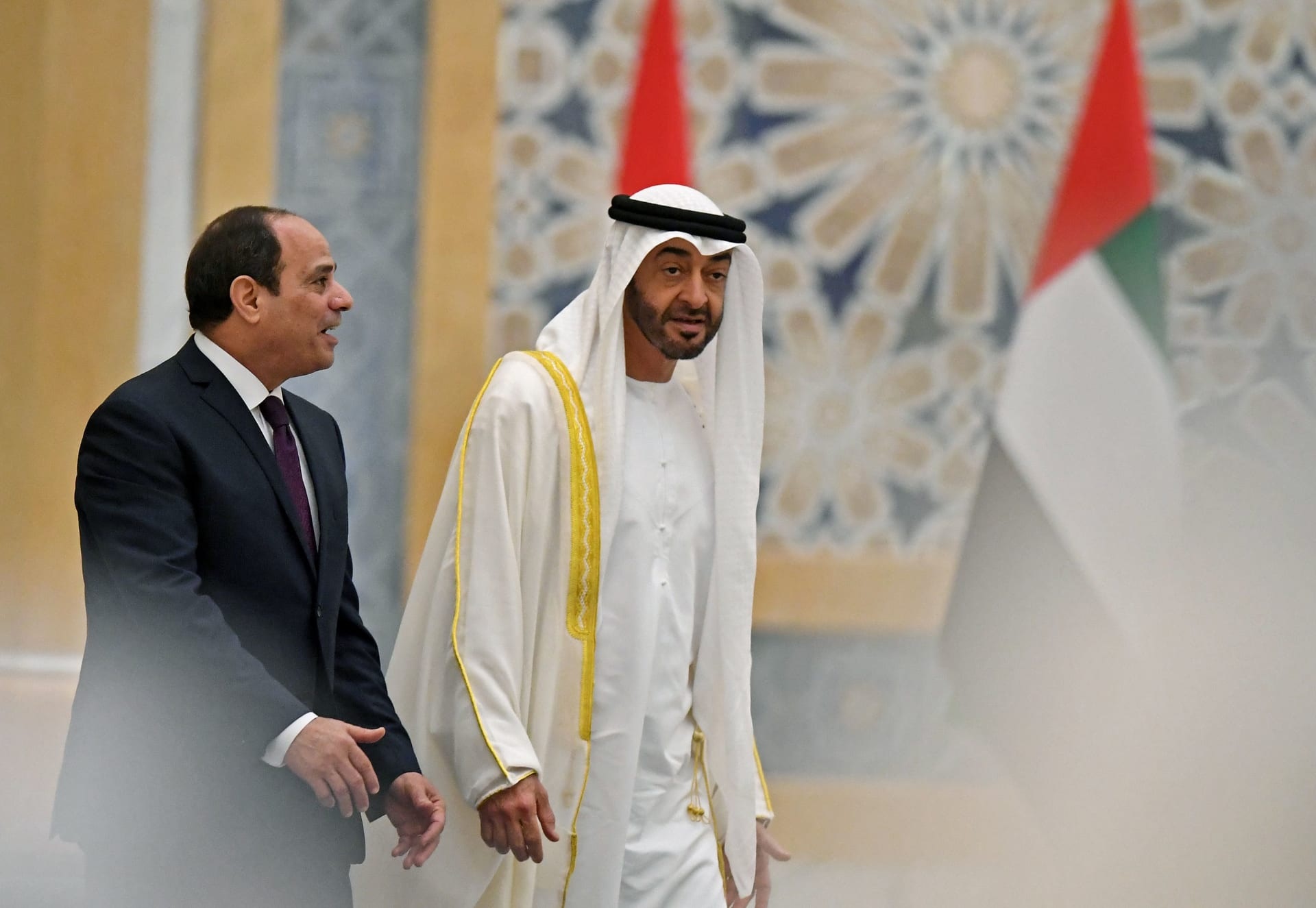

After rising to power in 2013 when the Egyptian military ousted the democratically elected Muslim Brotherhood government, President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi relied on Gulf states, particularly the UAE, for economic support.

The UAE has recently deepened its ties with Egypt through a historic $35 billion investment to develop the Ras El-Hekma area on the Mediterranean coast for tourism, providing a critical economic lifeline to Sisi’s regime.

However, despite this massive investment, Egypt remains unable to align with Abu Dhabi’s approach to Sudan. For Egypt, the military—not the RSF—is the cornerstone of stability along its southern border. This perspective is reinforced by Sudanese refugee movement patterns: a large number of refugees have fled to Egypt.

In recent months, Sudanese refugees have returned home from Egypt as the army regained parts of Sennar State and other areas in central Sudan, while mass displacement occurs whenever the RSF gains ground.

The stakes for Egypt are existential: since April 2023, Egypt has managed the flow of over 1.2 million Sudanese refugees, now the largest refugee community in the country. A complete state failure in Sudan could send millions more across the border.

Additionally, Egypt’s Nile water security hangs in the balance. The power vacuum in Sudan has severely weakened Egypt’s negotiating position with Ethiopia, its longtime rival in the Nile Basin.

For better or worse, Sudan has been a key ally for Egypt in countering the threat posed by Ethiopia’s Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD). In a recent statement, Sudanese Foreign Minister Ali Yusuf reinforced this alliance, pledging that “Sudan will stand with Egypt” and ominously stating that war remains an option if no agreement is reached.

But as Sudan descends into civil war and Egypt’s negotiating position weakens, Nile Basin states have seized the opportunity to advance their interests.

In a significant development, the Cooperative Framework Agreement (CFA) recently came into effect following South Sudan’s unexpected accession in July.

The agreement challenges colonial-era treaties that favored Egypt and Sudan by introducing the principle of “equitable use,” which greatly benefits upstream countries like Ethiopia.

With its weakened position on the Nile, Egypt has instead moved to build a regional security architecture encircling Ethiopia, forming a security alliance with Somalia and Eritrea. Crucially, Egypt’s foreign minister stated that Cairo would use this security alliance to help the Sudanese army combat “terrorism.”

Despite the UAE’s broad support for the RSF, its strategic goals in Sudan have been significantly undermined by the paramilitary group’s failure to seize control of the country.

The UAE’s plan centered on exploiting Sudan’s gold trade and enhancing its food security through state-linked land acquisitions.

A key element of this strategy was the $6 billion Abu Amama port project on Sudan’s Red Sea coast, designed to connect agricultural regions to an export hub and align with the UAE’s broader regional maritime strategy, complementing its port operations in neighboring countries.

However, the ongoing war has derailed these plans. Sudan has officially canceled the port deal, with the finance minister declaring, “After what has happened, we will not give the UAE a single centimeter on the Red Sea.”

Moreover, Sudan’s war has exposed a deep divergence in vision between Egypt and the UAE. Egypt views the SAF as the critical institutional backbone of the Sudanese state, reflecting its own model of military governance.

Cairo is thus firmly committed to ensuring the SAF’s stability and positioning it as the leading force in any future Sudanese government.

This vision excludes paramilitary groups like the RSF, which Egypt fears could reignite conflict along its southern border.

By contrast, the UAE sees Sudan primarily through an extractive lens, seeking strategic access to the country’s vital resources.

Within this framework, the RSF functions as a key enabler of resource extraction, with Dubai already serving as the primary destination for gold smuggled by militias.

Recognizing that it faces a well-funded force reliant on a foreign sponsor, the Sudanese government has agreed to hold direct talks with the UAE, but only on the condition that Abu Dhabi ceases its support for the RSF and pays “compensation to the Sudanese people.”

This offer presents a potential exit from the ongoing war, but it poses both financial and reputational challenges—even for the wealthy oil state.

The fighting has destroyed most of Sudan’s productive infrastructure, causing losses exceeding $200 billion. The UAE would be effectively obligated to fund Sudan’s reconstruction—the third-largest country in Africa—while simultaneously accepting the dissolution of the RSF, which has been vital to its economic and strategic interests, both in Sudan and as a mercenary force in key geopolitical theaters like Yemen.

Second, it would require the UAE to acknowledge its role in contributing to the world’s largest humanitarian and displacement crisis by arming the RSF—actions that starkly contradict its carefully cultivated image as a humanitarian benefactor.

Given the current situation, Egypt is well-positioned to play a crucial mediating role in bridging the widening gap between Sudan’s demands and the UAE’s continued narrative of denial.

Sudan’s foreign minister has already indicated that such an initiative is underway following the Egyptian foreign minister’s recent visit to Sudan’s wartime capital, Port Sudan—his second visit in six weeks.

The path forward, while difficult, is clear: it requires a meeting between Abu Dhabi and Cairo to finalize a near-term ceasefire and ensure Sudan’s long-term stabilization.

There is also an opportunity for the US to leverage its diplomatic influence in mediating between Egypt and the UAE, encouraging its allies to find common ground and prevent Sudan from descending further into crisis.

The alternative is clear—continued support for opposing factions will only deepen Sudan’s descent into a prolonged and increasingly brutal civil war.